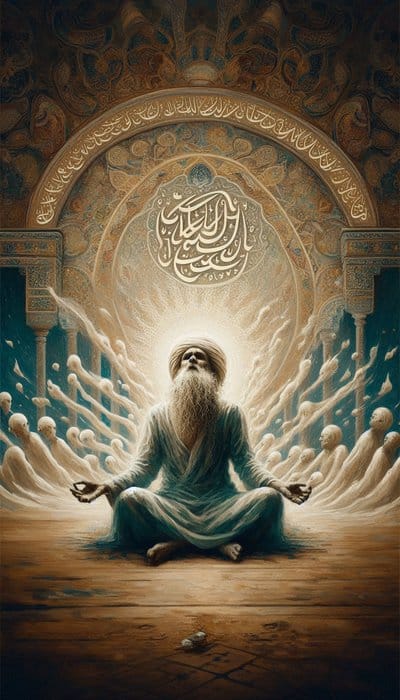

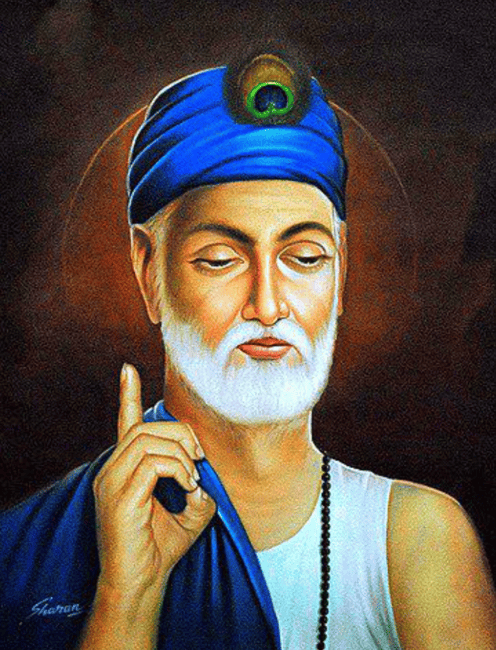

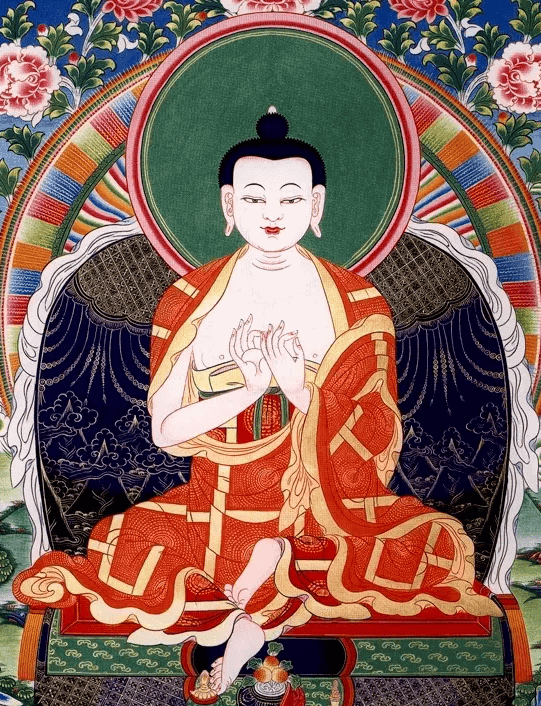

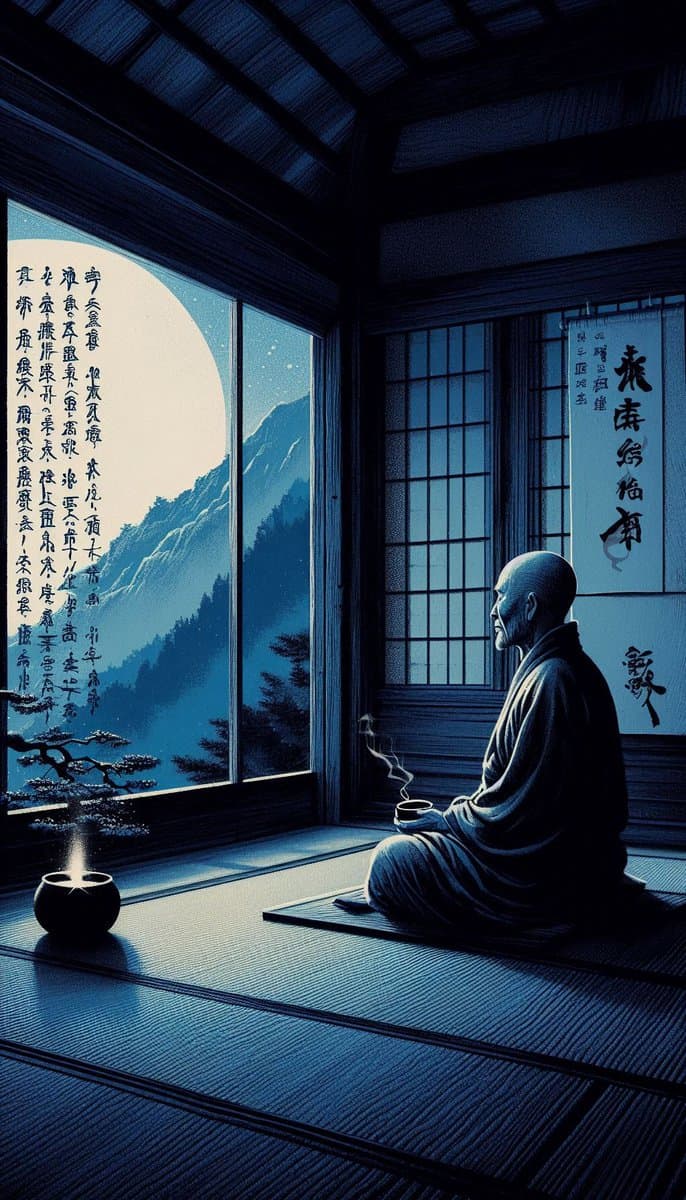

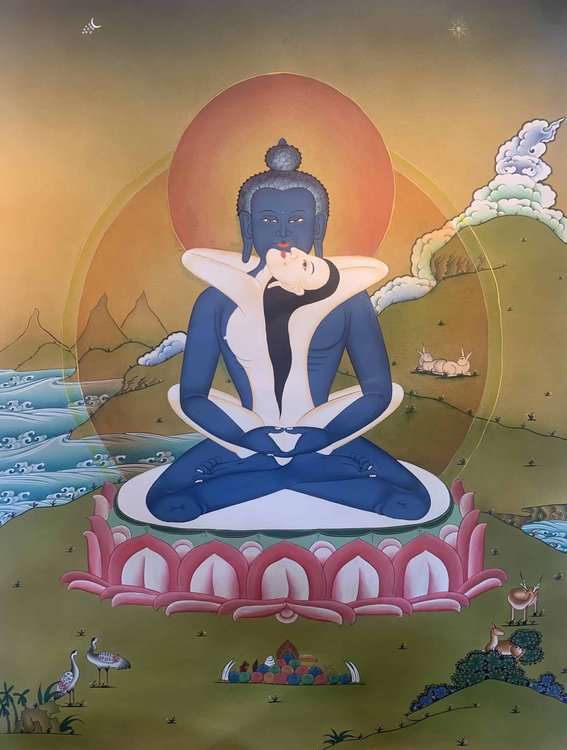

I saw my Lord with the Eye of my Heart – Al-Hallaj

I saw my Lord with the eye of my heart I said: ‘Who are You?’ He said: ‘You!’ But for You, ‘where’ cannot have a place And there is no ‘where’ when it concerns You. The mind has no image of your existence in time Which would permit the mind to know where you are. […]

I saw my Lord with the Eye of my Heart – Al-Hallaj Read Post »